“Inside The Business Side of Mail Pouch Signs – The Previously Untold Story of the Business Side of Mail Pouch Signs“

by Dennis Niederkohr – Spring 2021 and Summer 2021 editions of the ‘Mail Pouch Barnstormers’ newsletter

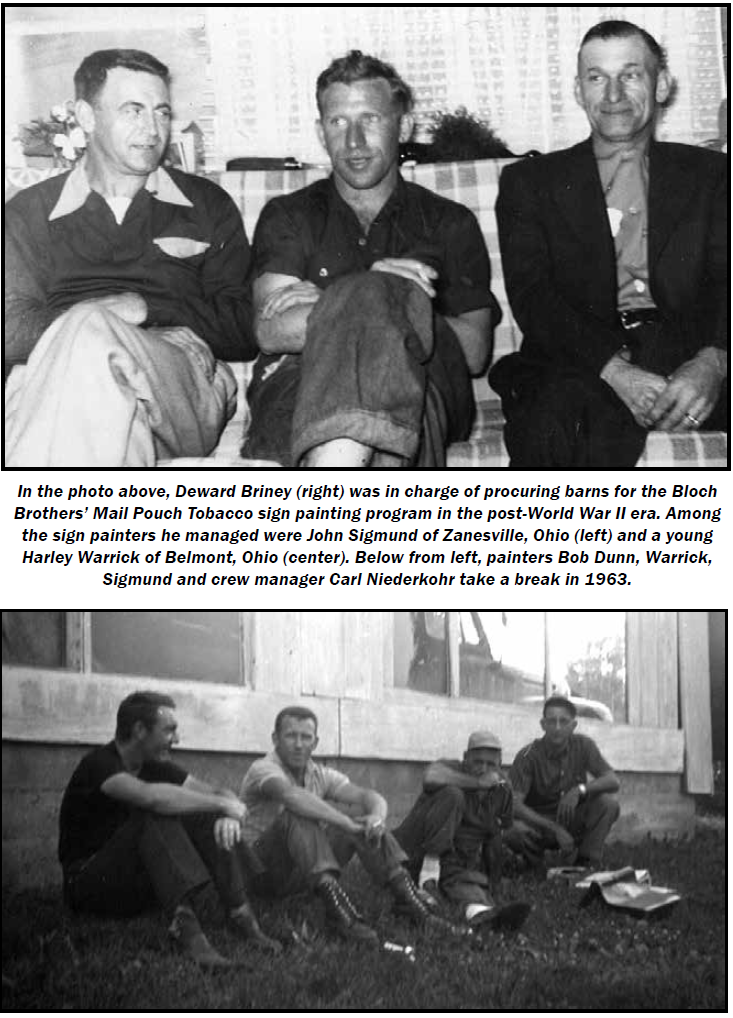

I am the son of Carl Niederkohr, the last outdoor advertising agent for Mail Pouch Tobacco and Bloch Brothers. I would like to tell you stories about the business side of the barn painting phenomenon to explain more about an amazing form of advertising America will never see again.

In 1879, Samuel S. Bloch, co-founder of Bloch Brothers Tobacco Company with brother Aaron, convinced farmers to accept a free coat of paint for their barn in return for advertising space on one side. These barns were first painted by E.W. Wrinkle. In 1915 W.H. Burner of Oakland, Calif., took charge of the

painting.

The procurement of barns for advertising Mail Pouch Tobacco has been based in our home city of Republic, Ohio, since before WW2. It started here with Burner obtaining the contracts to paint Mail Pouch new signs for Bloch Bros. and soon took in his brother Ed of Cleveland, Ohio. Ed met a woman from Republic, got married and soon brought his stepson (and my cousin), Deward Briney, into the business. Briney had worked for General Motors for years setting up new dealerships and when Ed died, Deward decided he would carry on the business by himself because W.H. spent most of his time in California.

This life suited Briney; he was single and enjoyed traveling, meeting people and conducting business. He was known as a nomad because he would pull a small house trailer behind his car, find a camping spot in the area he was going to work and stay there until his work was completed. His entertainment was fishing in any available stream or river he came across.

Painters would come and go because this type of life kept them from home for weeks at a time. It was not ideal for family life. Enter Briney’s two young hires for his painting crew. One was John Sigmund of Zanesville, Ohio. The other was a very young Harley Warrick of Belmont, Ohio.

When conducting business, Briney would always wear a suit and tie, and a fedora hat that he would tip to the people he met.

On Aug. 18, 1961, Briney met his untimely death in Cambridge, Ohio, when his car collided with a loaded dump truck. Briney was to meet his painters and pay them for the week and pickup their square footage slips for the next pay period. He carried his payroll in cash and after the collision the trucker said Briney left his vehicle, opened the trunk, placed the locked briefcase with the money in the trunk and closed it. He then returned to the front seat, passed out and never awoke. My dad went to Cambridge and took the payroll to the painters along with the bad news that Briney was gone.

It was at Briney’s funeral in his huge 14-room home that my father was offered the advertising job by Stuart Bloch. My father accepted. Dad also owned an Allis-Chalmers farm implement dealership that his lead salesman managed when Dad was on the road.

Dad knew all the painters from the past years when they would come to Briney’s to visit while working the area (or if Briney hired them to paint the miles of hand-built white fence surrounding his farm).

There were two paint crews with two men to a crew. Bob Dunn was the youngest of the painters. Then came Harley, John Sigmund and Henry “Swalley” Apostolick. Harry Baugh was hired later to take over for Bob Dunn when Bob gave his notice.

Dad worked eight states leasing barns and meeting the crews to pay them and give them the lease slips for the new signs to be painted and any repaints. He would leave home for up to six weeks at a time. Mom and I made the best use of the time he was home, but his work was not over.

We would pick up pigment at Sherwin-Williams and bring it home to mix for the crews. The white, yellow, blue and red colors were purchased in five-gallon metal buckets and weighed 125 pounds per bucket because it was lead-based pigment. We had a special hand-held mixer that turned the pigment from a cakey to a creamy consistency. This was then mixed with linseed oil to make the paint we all recognize.

The black was purchased as lamp black, a by-product of charcoal production, that came in 50-pound plastic sacked boxes. This powder had the feel of face powder but once on your skin it went into your pores and it was a chore to wash it off. The boys on the crew mixed the black with linseed from on-board tanks.

The vehicles they drove were blue panel trucks and Harley named every one of his trucks “Magoo.” As the trucks got older he would then paint “Magoo” on the side of the truck.

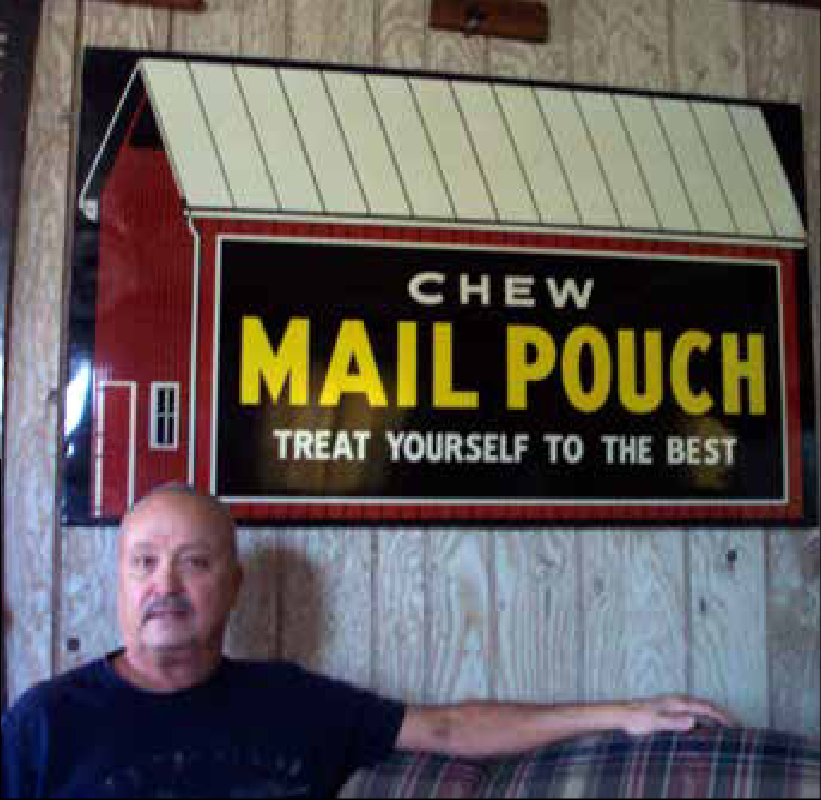

At least once a month I would help Dad erect road signs using a chain saw-driven post hole digger. The signs were usually mounted on four-inch diameter cedar posts and were local to Ohio due to the amount of material and size of the signs that had to be carried in the advertising vehicle. People from other states have never heard of this type of Mail Pouch advertising.

The signs were painted metal with woodback framing and came in sizes three-by-five or fourby

six-foot. Signs would be located on roadways going into major towns where they could be seen for a lengthy period of time. It was nice to put them next to a stop sign so the Mail Pouch sign could be seen longer. (As a side note: when Dad passed away, he had 57 of these signs in his basement. Over the years we sold them one at a time through auctions and garage sales. The good new signs that were never mounted sold for up to $3,500 each. He also had 13 six-foot Mail Pouch thermometers averaging $1,000 to $2,000 each. And he had 10 three-foot thermometers).

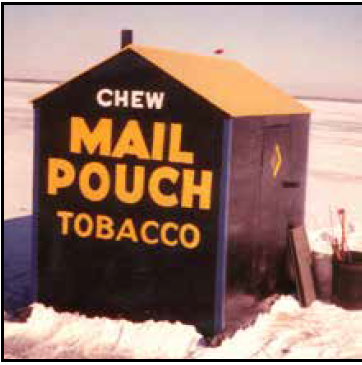

In the winter when Dad was home a bit more, he loved to go ice fishing on Lake Erie. In 1963 we built a beautiful wood ice shanty. When Harley came to visit he thought the shanty might look good with a Mail Pouch sign on it. Sure enough it did. It’s long since gone, but the memory lives on.

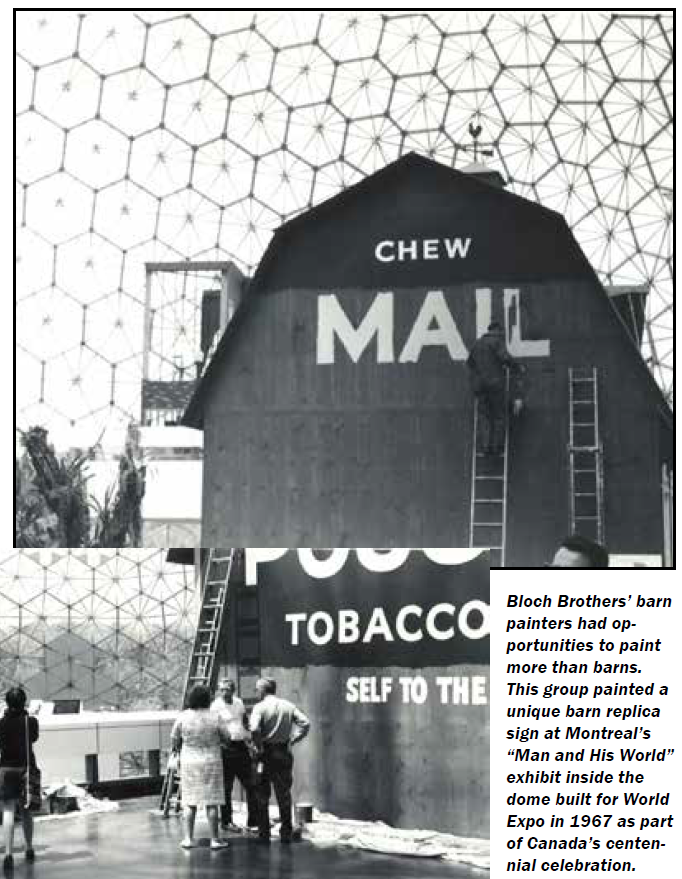

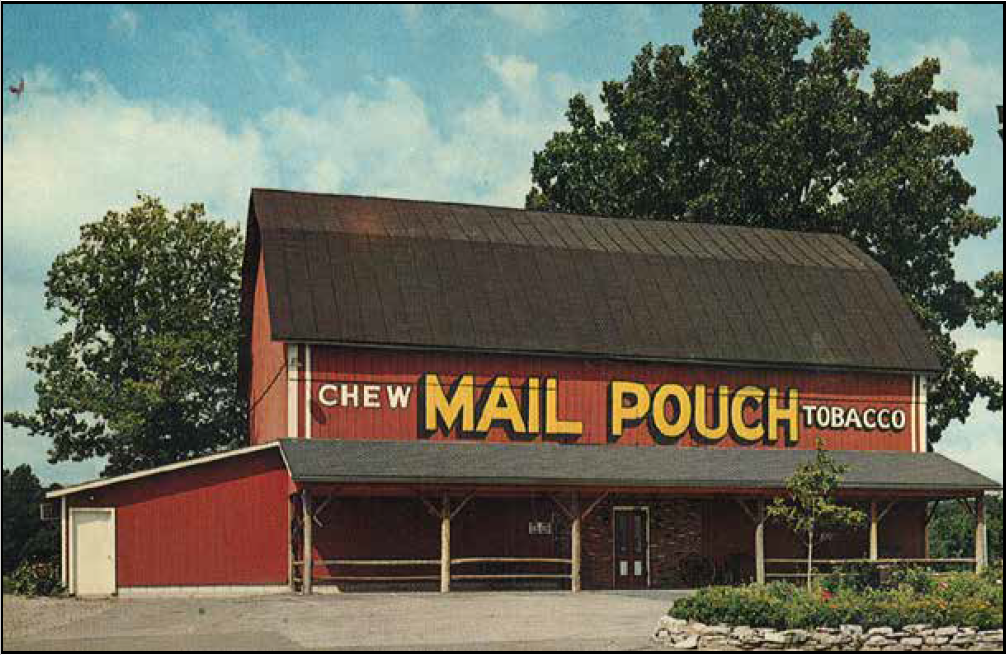

Dad would get requests from locals and from Bloch Brothers to do special projects. Two of these projects were at eating establishments. The first, at Wood’s Steer Barn restaurant in Upper Sandusky, Ohio, still operates to this day. The barn was built in 1897 and converted to a restaurant in 1965.

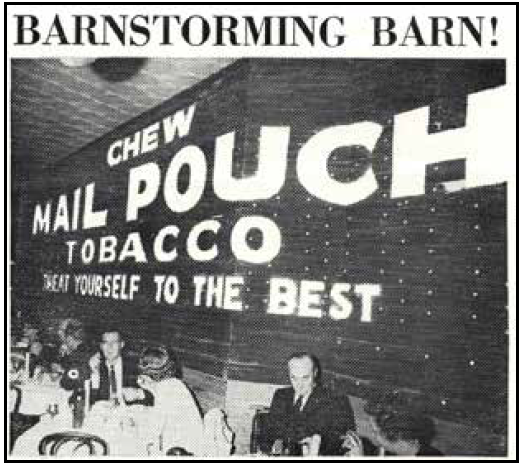

The second restaurant was The Sign of the Dove in Manhattan, N.Y., and was owned by Dr. Joseph Santo, a New York dentist, who thought a Mail Pouch barn sign inside of the restaurant would make an eye-catching conversation piece. Dad found a beautiful barn end in Clyde, Ohio. He bought it and sent

a crew to disassemble the sign and ship it to New York. Sadly the restaurant is no longer around.

There were thousands of stories involving these guys and their barn painting adventures. Did you hear about the time a pesky hog was scratching itself on Harley and Bob’s ladders and wouldn’t leave? They wrestled it to the ground and painted it like a zebra. Dad and Stuart had to buy the hog because it couldn’t be marketed with lead base paint on it.

Did you know occasionally Harley would misspell a word just to see if people were paying attention?

He would change the word Treat to Treet and the word Yourself to Yerself or reverse the words “to” and “the”.

Several times before leaving the job, Harley would paint a window in the bottom corner of the barn

with a cow’s head sticking out the window just to break the monotony.

The guys would get a kick out of a farmer who wanted to paint over a Mail Pouch sign because

he didn’t want it anymore. What the farmer didn’t know was that linseed oil soaks into the wood and

crystalizes. When someone would try to paint over it, the new paint would soften the linseed oil and the more dominant oil would bleed through the cover coat and just eat it up. In just a couple of days you

would see the letters bleeding through, followed by the background colors. In a month’s time the sign would be back in all its glory. When asked how to paint it out the standard answer was “with a brush.

My father would get called to Wheeling twice a year to discuss business at Bloch Bros. Tobacco with Stuart Bloch. While in Wheeling he would pick up three cases of Mail Pouch chew and a case of Kentucky Club to give to customers.

Dad had me try the chew and I’m telling you, you had to be a man to enjoy that tobacco. It was not sweet by any means so I never developed the habit.

Every year Dad and Mom would have to go to West Virginia to put tax tags on every tobacco sign in the state. This would take them two weeks plus. Old tags had to be removed and new ones were put on in a location where the tax authority could see it with a pair of binoculars. Each year was a different color and/or a different size.

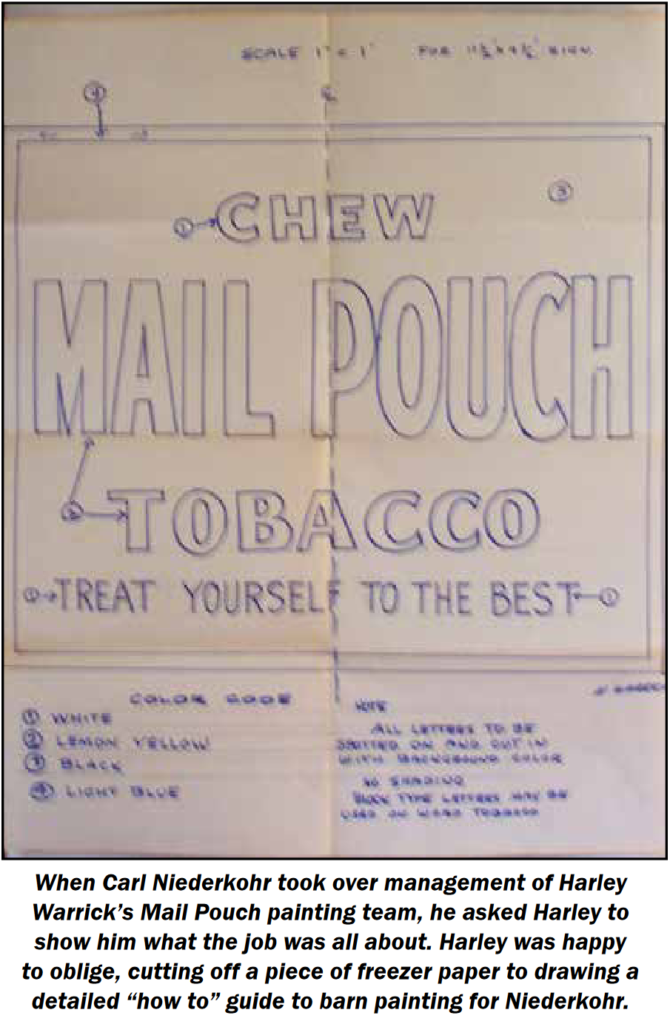

When Dad took over for Deward Briney after Briney’s death, he asked Harley if it would be okay to work with him for a week to see what his end of the job entailed. Harley was pleased that my dad wanted to do this because no one else took an interest in Harley’s side of the business.

Harley cut off a piece of freezer paper and drew this detailed “how to” step by step guide to barn painting for Dad (it is signed by the master himself).

In addition to painting, the crews had to do a lot of carpentry work because a lot of the old barns had siding missing or just laid loose on the barn and had to be re-nailed.

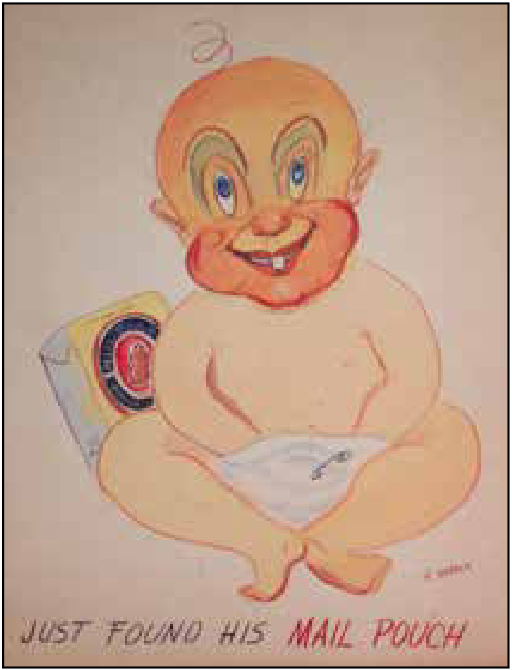

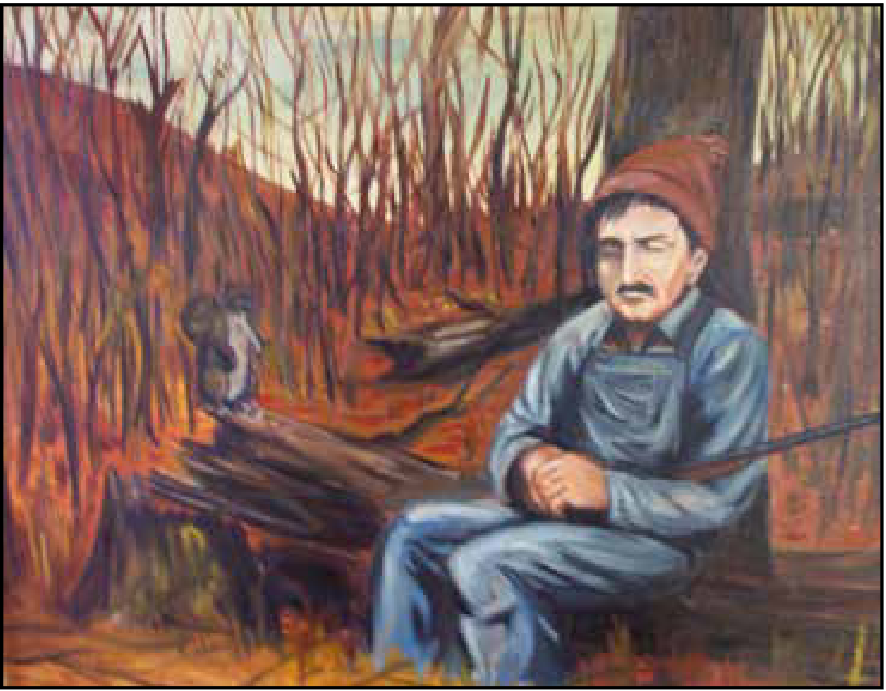

In Harley’s off season, he would paint pictures to keep himself busy. He didn’t paint many pictures of Mail Pouch signs because he did that every day. Lady Bird Johnson’s beautification act hadn’t kicked in yet so his relaxation consisted of landscapes, funny portraits and whatever else took his fancy. Most of these paintings were given to friends and relatives. Hopefully everyone kept them for posterity. My family sure did.

Harley loved scenery and the countryside as evidenced by the majority of his paintings. The first one Dad received was painted by Harley in 1963.

On occasion he liked a little whimsey. One of my favorites is the Mail Pouch baby. Notice the baby’s drawing is patterned off the real advertising card. Dad would hand these out to customers if and only if he knew they wouldn’t be offended. He probably couldn’t do that today due to moral correctness.

My dad’s business card that he gave to everyone to introduce himself was all about being real and genuine with the customers. Many times, he would be invited to supper and after they would want to know all about his travels. One lady in Kentucky always had pie and a cup of coffee for Dad and was just glad to have someone to visit with. Sales was always 40 percent knowledge and 60 percent personality and my dad was big on personality, as was Harley. I think that’s why they got along so well together.

The last piece of art that I have from Harley is a painting he did of Briney squirrel hunting while he was sleeping under the tree. This one hung in Briney’s office for years because he thought so much of it. Our family was lucky to obtain it after Briney’s death.

When Mail Pouching was over for Dad, the equipment and trucks sat in a storage building on our property for over a year. We sold one of the trucks to a local tree trimmer, but “Magoo” – Harley’s truck – and all the equipment, paint, ladders, stages, oil and everything else stayed idle. Harley called one evening and asked if Dad would consider selling all of it to him for repaints that the company wanted him to do. Dad made a special low price and Harley was off on his own. The rest, as they say, is history.

For those of you that have never seen a metal outdoor Mail Pouch advertising sign, mine hangs in my living room. I wanted to hang this in 1988 but my wife said if I did, she would leave. I hung it and my second wife loves it.